Machine Learning Development Using Behavioral Analysis

A behavioral safety-driven use case for developing ML models for automated driving features guided by novel safety standards

Introduction

One of the most significant challenges in modern automotive safety is the safe development and deployment of systems that rely on non-deterministic Machine Learning (ML) components. As the industry moves toward automated driving functions that depend heavily on perception, planning, and control algorithms powered by ML, traditional safety approaches must evolve to ensure predictable and acceptable vehicle behavior across complex operational environments.

From a safety engineering perspective, the problem is not only verifying that software operates without faults, but also ensuring that learned behaviors remain safe under a wide variety of real-world conditions. This introduces challenges addressed by functional safety (ISO 26262), safety of the intended functionality (ISO 21448/SOTIF), and more recently AI-specific safety lifecycle guidance such as ISO/PAS 8800.

Based on practical experience integrating safety across multiple organizations deploying ML-enabled systems, this article describes a structured behavioral safety approach that bridges system definition, scenario analysis, model development, verification, and validation. The intent is to demonstrate how safety-driven scenario engineering can guide both ML training and validation while ensuring alignment with industry standards.

1. General Approach: Behavioral Safety as a Systems Engineering Framework

Behavioral safety focuses on defining and validating how a vehicle should behave safely across its Operational Design Domain (ODD) rather than only analyzing system malfunctions.

Traditional functional safety processes such as HARA (Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment) focus on identifying hazards caused by failures. However, automated driving introduces risks even when systems operate as intended but insufficiently — a core concern of SOTIF and AI safety.

The proposed approach begins with:

Clear definition of the system’s ODD.

Identification of vehicle capabilities or behaviors (e.g., Adaptive Cruise Control, lane keeping, lane changes, collision avoidance).

Definition of safe behavioral expectations across operating contexts.

Behavioral safety therefore acts as a bridge between:

DisciplinePrimary FocusISO 26262 (FuSa)Malfunction-related hazardsISO 21448 (SOTIF)Performance limitations and insufficienciesISO/PAS 8800AI lifecycle and data-driven safetyBehavioral safety approachSafe vehicle behavior across scenarios

Rather than treating safety as an activity occurring after development, this framework embeds safety criteria into scenario definition, data selection, model training, and validation.

2. Scenario Definition Based on ODD and Vehicle Behaviors

The first step is identifying scenarios derived from:

ODD characteristics:

Highway driving

Surface streets

Environmental conditions

Traffic participants (vehicles, VRUs, infrastructure)

Behavioral capabilities:

Adaptive cruise control

Lane keeping

Lane changes

Obstacle avoidance

Emergency braking

These represent vehicle-level requirements rather than safety analysis alone. The objective is to define what the vehicle must do and where it must do it.

Example:

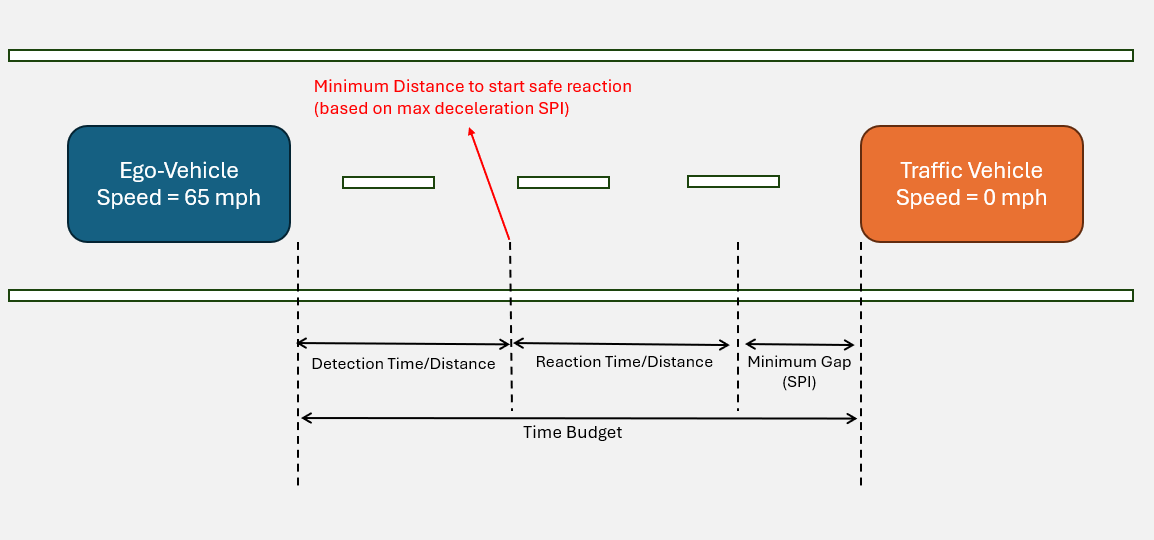

A highway scenario:

Ego vehicle traveling at 65 mph

Lead vehicle stationary

Clear visibility

Standard highway geometry

This scenario becomes a reference point for defining expected safe behavior.

3. Scenario Analysis Using Safety Performance Indicators (SPIs)

Once scenarios are defined, behavioral safety analysis evaluates safe performance expectations using Safety Performance Indicators (SPIs).

Typical SPIs include:

Minimum time-to-collision (TTC)

Minimum distance to obstacle

Maximum acceleration/deceleration limits

Comfort and stability thresholds

Reaction timing constraints

Example analysis:

ParameterExample Safe ConstraintMaximum deceleration−5 m/s²Minimum following distance≥10–20 mTTC thresholdAbove defined safety marginDetection range requirement≥150–200 m for stopped vehicle

The analysis answers:

When must the vehicle detect the hazard?

When must braking begin?

What trajectory constraints must be respected?

These behavioral expectations directly translate into:

Perception requirements (detection range, classification confidence)

Planning requirements (trajectory generation)

Control requirements (actuation limits)

4. Safe Behavior Definition Across the ODD

Aggregating scenario analyses produces a structured set of safe behavioral requirements.

This resembles HARA in methodology but differs in intent:

HARABehavioral Safety AnalysisFocus on faultsFocus on expected safe behaviorFailure-based hazardsCapability-based safety expectationsSafety goalsBehavioral performance requirements

Outputs include:

High-level abstract scenarios.

Safe behavior specifications.

Operational constraints tied to vehicle capabilities.

These define what “safe operation” means beyond simply avoiding failures.

The scenario image below describes a specific scenario relevant for our ODD. In this scenario, we analyze against SPIs for maximum deceleration and minimum distance to a stopped vehicle. So the questions we are answering by doing this analysis are

At what point does the vehicle need to start decelerating in order to stop at a safe distance from the stopped vehicle?

And the above leads to the question, at what point does the SDT need to detect the stopped vehicle such that it can start decelerating at the minimum distance to safely execute longitudinal deceleration to stop at a safe distance?

This approach is followed for all the safety relevant scenarios within our ODD across behavior capabilities, which gives us a set of relevant abstract scenarios for parametrization in simulation.

5. Scenario Parameterization for Simulation

High-level scenarios are converted into concrete, parameterized simulation cases.

Parameters may include:

Speed ranges

Distances

Sensor noise levels

Traffic density

Environmental variability

Simulation environments (e.g., CarMaker, CARLA, proprietary tools) allow systematic exploration of scenario variations within the ODD.

This stage transforms safety analysis into executable engineering artifacts:

Training scenarios

Validation datasets

Verification test cases

6. Model Training Using Safety-Driven Simulation Scenarios

Machine learning models are trained using scenarios derived from safety analysis.

Key principles:

Training data represents the ODD.

Safe behaviors define desired outputs.

Simulation enables coverage of rare or safety-critical cases.

Example workflow:

Abstract safety scenarios defined.

Parameterized into simulation.

Simulation generates data aligned with safe behavioral constraints.

ML model trained (e.g., imitation learning for trajectory planning).

This approach ensures:

Safety expectations guide model behavior from the beginning.

Reduced risk of late-stage retraining due to missing safety coverage.

7. Verification and Validation Across the Lifecycle

Behavioral safety scenarios become the backbone of verification and validation:

StageUsageSimulation testingInitial validation of model performanceSoftware-in-the-loopFunctional validationHardware-in-the-loopIntegration testingClosed-course testingControlled real-world validationPublic road testingOperational validation

Each scenario includes measurable expected behavior, enabling objective pass/fail criteria.

8. Alignment with ISO/PAS 8800 (AI Safety Lifecycle)

ISO/PAS 8800 emphasizes lifecycle control of AI systems, particularly:

Data lifecycle management

ODD representativeness

Training and validation dataset relevance

Verification of learned behavior

The described approach aligns naturally with these principles:

ISO/PAS 8800 ExpectationAlignment in Proposed ApproachODD-based data selectionScenarios derived directly from ODDTraceable data lifecycleSimulation scenarios linked to safety analysisRepresentative training datasetsParameterized scenarios ensure coverageValidation against expected behaviorSPIs define measurable safety criteria

By integrating safety-driven scenario engineering early, ML development becomes traceable and auditable from data generation through deployment.

9. Benefits and Practical Motivation

A common industry challenge is allowing ML development to proceed independently from safety engineering, resulting in:

Misalignment between model behavior and safety expectations.

Late-stage redesign or retraining.

Increased development cost and risk.

Embedding behavioral safety into the development lifecycle:

Reduces iteration cycles.

Aligns system engineering and ML workflows.

Enables early identification of gaps between intended and learned behavior.

10. Applicability Beyond ML Training

This approach extends beyond ML development:

Risk assessment (ISO 26262 and ISO 21448).

Test scenario generation.

Safety case evidence.

Runtime monitoring design.

Performance benchmarking.

Conclusion

Behavioral safety provides a practical bridge between traditional automotive safety engineering and modern ML-driven automated driving systems. By defining safe behaviors through systematic scenario analysis and using these scenarios to drive model training and validation, organizations can integrate safety throughout the lifecycle — from data generation to vehicle deployment.

Aligning scenario engineering with ISO 26262, ISO 21448, and ISO/PAS 8800 ensures that safety is not an afterthought but a foundational element guiding system behavior, ML development, and verification.

Summary

Behavioral safety defines safe vehicle behavior across ODD scenarios rather than focusing only on failures.

Scenario analysis using safety performance indicators translates safety expectations into engineering requirements.

Parameterized simulation scenarios drive both ML training and verification.

The approach aligns strongly with ISO/PAS 8800 by ensuring ODD-representative datasets and traceable AI lifecycle processes.

Integrating safety early reduces development risk and improves ML deployment readiness.